Recording and Linking Millions and Millions of Notes (or at least a few)

Mastering Note Processing: Lesson 3

“Fatique makes cowards of us all.”

Vince Lombardi

One May Be The Loneliest Number, But What A Mess is Three!

I love two activities more than any other: bringing order to a messy situation and making a mess of order. Chaos and order. War and peace.

This post is about peace and war, order and chaos, home and the woods, marriage, family, friendship.

Other than that, nothing much.

Because:

Fast behind Your First Note furiously follows your second. Then suddenly your third and fourth and 153rd. Notes multiply like a Mennonite’s grandchildren. One becomes many, chaos threatens order, and family life and friendship become battlegrounds (unless you are a Mennonite).

Soon, if you aren’t careful, you’ll have so many notes rolling around the floor and the shelves and climbing the walls and the ceiling that you won’t be able to find anything.

But that was why we developed this system for note-processing: to find things!

It’s time to deal with the mess.

But first let’s learn how to make it!

What’s New?

What are we going to learn in this lesson? Two things: how to write more notes and how to deal with the mess those notes generate.

And what is the point of this note? Briefly this: While notes are easier to write after the first, adding them makes note-processing more complicated.

Adding notes

You probably think you are going to write your 2nd and 153rd note the same way you wrote Your First Note, and you’re pretty right to think so. Much is the same:

You will continue to have access to three kinds of Destination Notebook: J, P, and Q

You will continue to draw notes from three sources: your thoughts, spoken words, and written words.

You will continue to write one of three kinds of note: quotations, responses, and ruminations.

You will continue to index your notes and add them to your table of contents

You will continue to write notes on pages freshly arranged to receive them in their warm embrace

You’ll even continue to have the same challenge: decision-fatigue.

In the earlier lesson you learned one great way to minimize this annoyance: avoid having to make decisions at the last minute when you can make them ahead of time.

In other words, prepare your destination (the notebooks), have sources at hand (words spoken, words written, and words thought), and keep your tools ready (pens, indices, TOC’s, pages).

Sources, destinations, and tools help you clear your head so when new challenges arise you will be ready for them.

And yet…

A New Challenge

As soon as you introduce your second note, you have changed everything completely, totally, utterly, infinitely, and, for the coup de grace, more than a little bit.

Seconds change the world!

Think of the story of Adam and Eve. “It is not good for the man to be alone,” says the ancient scripture. So the Lord made the first knock out. Literally. He knocked Adam out and made Eve out of his rib.

This led to the first dad joke when Adam said to Eve, “Don’t rib me,” at which she established precedence by rolling her eyes and saying, “Don’t kid me.”

Here was a new opportunity for the formerly lone ranger alone on his lonely range. And here was a new set of, shall we say, challenges?

Adding one to one certainly equals two, but in the realm of relationships it often, if not usually, leads to multiplication.

A Digression on How Adding One’s is Multiplication

Let me give you an example. When I was a young’un, I read heady books with a lustful zeal. By heady, I mean boring: like college psychology texts or word studies (me and words, we got a thing going on). I also mean hard, like Dostoevsky or Dr Seuss.

In my untrained greed, I took to highlighting, thinking it might help me remember more, follow the flow of thought, and look clever. Because I had seen others do it, I highlighted in yellow. A lot.

After a few days (or maybe it was years, I don’t remember), I was disturbed to discover that it didn’t help very much if the whole page looked like yellow snow. My first instinct was to highlight less, so I did. Frankly, that helped.

A bit.

But not enough.

As Plato’s Socrates famously said, necessity is the mother of invention. So I called my mother and asked her what I should do.

She suggested something so radical and extreme I could hardly believe my ears. Use different colors for different purposes, she said.

You have probably got the impression from reading my bold posts that I am a very daring reader, and you are right. I read lustily, brazenly, like reading is a blood sport. I read to kill.

So when mother necessity told me to use a second color, I rushed, pen in hand, to the nearest desk drawer, yanked it off its slides, and reached in to seize a highlighter that I might return, defy the honor of the text, and torture it to reveal its secrets.

The problem was, since this idea was so revolutionary, there was no second color in the desk drawer.

I was forced to wait till I could get a ride to the school supply store.

Finally, a week or two later, my father pulled into the carriageway with the wagon, and, before he could hitch up the horses I shot out of the house like a bolt into his chest.

Which meant my mother had to bring me to the store. This was not convenient, but it was necessary, so she brought me. Thus I bought my first colored highlighter, a green one.

From that day, I began to highlight in green what philosophers came to call “meta-discourse”, reminding us why we hide them away in the colleges.

When an author wrote something like, “There are three reasons you should highlight in more than one color,” I and my green gun were ready for him. When he wrote, “The first reason,” I was first with the green. When he said “The second reason,” I seconded with green. When he said, “153rd” — well, by then I had fallen asleep, but I think you get my point.

In my greener days (Oh, that’s ironic!) when I would highlight in yellow, I didn’t pay much attention to why I was highlighting. I just did it. If something seemed highlightable I highlighted it. I didn’t analyze or read all that closely.

When I added green, everything changed completely, totally, utterly, infinitely, and even, more than a little bit. I entered my salad days (these keep sneaking up on me. I’m truly sorry).

Now I had a specific reason for using green which differed from my reason for using yellow. In fact, because I had a reason for green, I found myself asking why I used yellow.

This led to another peculiar discovery.

I noticed that my head walks around with a bag full of questions that it wants answered no matter what I make it read. It was like my mind had a job to do and it wasn’t going to help me do my job unless I helped it do his, which was fine because he was only doing his because I asked him to but he did apparently insist on doing it his own way. If you see what I mean, or is it what he means?

For example, my mind always asks, “Does this creep - er, I mean author - use dysermeneutos1 words?” or “Does he say anything memorably?” or “Do I agree?”

Having gone green, it was easy to see that I could use other colors as well. I could easily turn Orange Man (for things about which I was dubious), to dress in pink for reference (names, dates, places, dysermeneutos words, etc.), and to share my blues (bon mots, mot justes, and other french stuff that means, “this sounds good” - stuff that often gets stuffed in Q).

Next thing you know, I had a five color highlighting system that lets me do all sorts of things that are considered advanced reading skills, like pre-reading and trying to understand what I’m reading.

All because I bought a second color.

Now I admit that my scheme drives some people batty when they see it, but I have taught it to teachers and high school students and many adults and students have thanked me for it. Most surprisingly, at least to me, has been kids with reading challenges and their parents reporting that they find it helpful. All this time, I thought I was developing a useful system because I was such a brilliant killer reader and it turns out I was special.

Oh well.

The body is the mind’s best servant. The more of your body you use to read, the more your mind will absorb.

Anyway, the point is, the second highlighter was conceived by necessity, but after that, the other highlighters flowed freely like water colors in the rain.

Similarly, once you add the second note, the third, fourth, and forever-after-note will flow naturally. And everything will change, completely, utterly... and so on.

The hardest thing of all is to think of something never done before: “A One.”

The second hardest thing is to make a second One that proceeds from the first One, One that is both like it and different. “And a two.”

But once the second has proceeded, begetting thirds and fourths and 153rd’s is surprisingly easy. “And a one, two, three, four.”

Something New Has Been Created

I took a long time to describe Your First Note. In fact, before I could show you how to create it, I had to show you how to make a world that would be home to it—dividing light from dark, land from sea, air from water.

It won’t take as long to describe how to record your second and third notes.

But there’s a challenge.

With all that creation and generation and multiplication, a new reality has come into being: relationships.

That’s Not Only Good News

Think of it this way.

Decision-fatigue is a thing because decisions are tiring. But why do we have to make them?

Often we have to deliberate because a new thing has disrupted our peace and quiet. What used to be stable and single is now in a relationship? And that means change, adaptation, dancing, foot-stomping.

Does not every offering of greater harmony threaten us with the risk of discord? Aren’t the joys of harmony intensified by the right proportion of discord? Isn’t discord risky and therefore scary? Don’t we fear unmanageable change, disproportionate multiplicity, the risk of chaos?

Change, discord, and resolution applied to thought require deliberation and judgment. And that means decisions.

And that means fatigue.

Chaos is exhausting.

It even effects our mental health.

So I want to offer you this series for more than just Note-Processing. Let’s lift it up a level and turn it into an exercise to bring harmony to our minds and even, as much as possible, to our relationships.

How? By attending to the relationships between and among our notes, we can establish patterns that will, I hope, bring you some degree of peace of mind and the joy of a resonating chord.

Then, by attending to those patterns, we can level them up to our personal relationships, bringing a degree of peace, joy, and resonance when discord and chaos threaten.

Neither notes nor people are easy to keep in harmony, but the effort is worth it.

So to summarize where we’ve got so far.

I like order and I like messes. Your notes will be easier to write now that you’ve completed Your First Note. But a new challenge has arisen: more notes means more relationships.

The difference, then, when we have more than one note is that we have introduced the potentialities, the wonders, and the challenges of relationships.

The Third Hand

That’s a musical term. I’m using it to direct your attention to the fact that for the rest of our series, you will practice and wrestle with three things:

Generating notes from sources

Recording notes in destinations

Relating notes to each other

That’s pretty much it.

Enough exhortation; it’s time for action.

Let’s Get Musical

If you want to maintain a relationship with another person, you need to communicate. If you want to communicate with another person, you need to know where she is and you need a way to get either yourself or your message to her where she is.

Think of notes the same way. One note cannot communicate with another if One doesn’t know where Other is and doesn’t have a way to get There.

Sometimes, One and Other live in the same house, sometimes in the same neighborhood, city, country, or planet.

As they move farther apart, addresses, packages, and vehicles become intensely important. Downright necessary. Time to call on mother again!

Ah, but she already told us what to do. The house corresponds to the notebook. If One wants to join up with Other in the same house, she can just walk down the hall or, if your notes are unmannerly, shout.

To put it more helpfully, if both notes are in the same notebook and you want to introduce them, you link them by adding a pointer and a page number: an arrow that points to the page or “room number.”

I suppose you want to see one. OK, fine, but I have to say this feels like an invasion of my privacy, barging into my room like this.

“Here!” I pout “look down at the lower right—but nowhere else.”

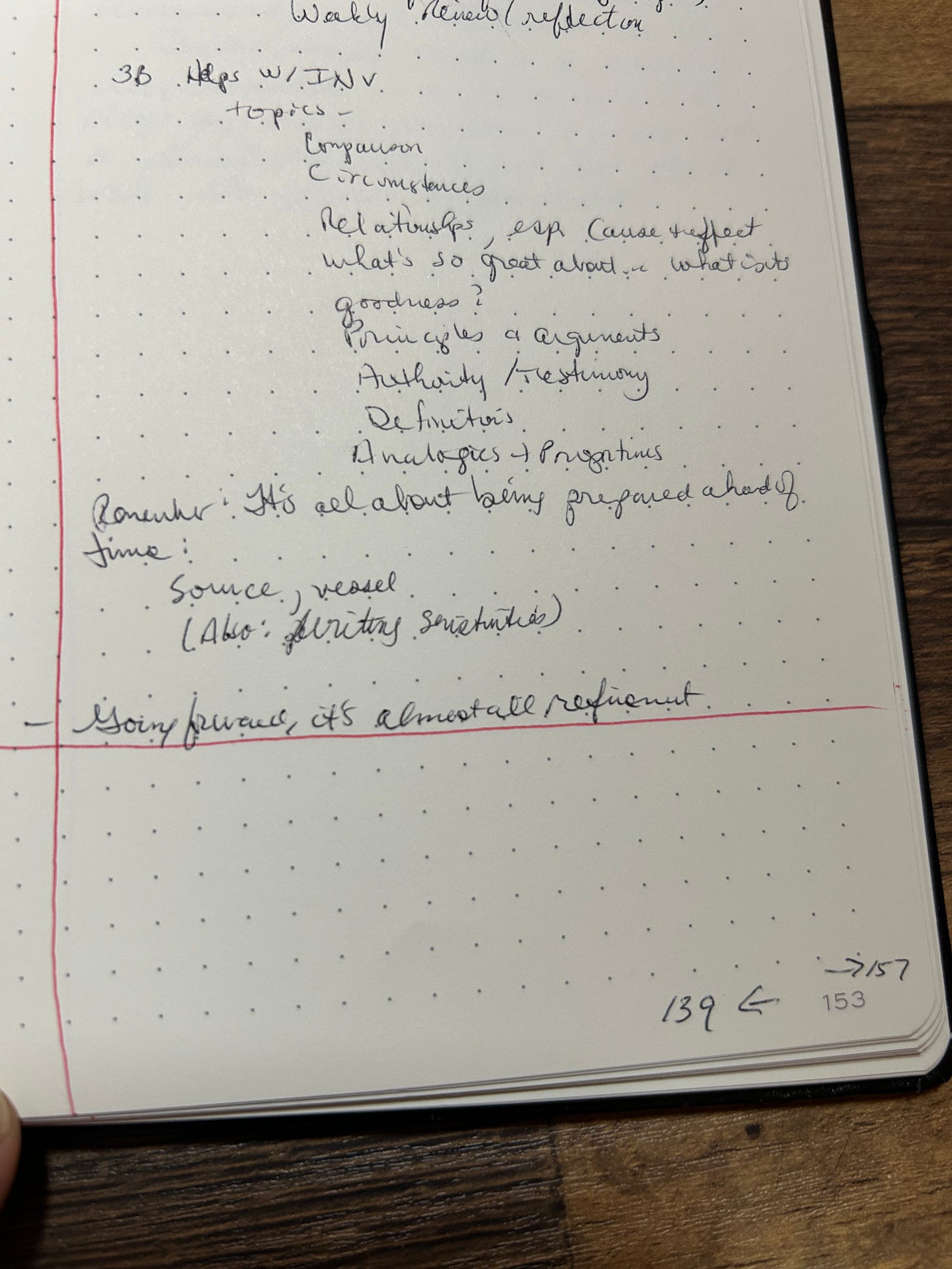

See that, down in the lower right hand corner? This note is on page 139, but I continue it on pages 149 and 153, so I link it to those pages.

Both of those arrows point to later pages (that is why they point to the right), but sometimes a note will link to an earlier page. In the next picture, you’ll see that page 153 points back to page 139.

But wait! There’s more!

The pointers can go in both directions, which you’ll also see in the next picture:

The pointers can go in the middle of the page too, but I won’t show a picture because I know how overstimulating pictures can be online, especially masterpieces like these.

Also, stop looking at the rest of my page and keep your eyes where they belong. Those notes are for later so you have no business looking there!

Now, if I have your attention back up front, I’ll remind you that we were learning how to move around within a single notebook, which I compared to a house (Sorry about having to number the rooms. It’s a big house so names don’t quite work).

What about notes in different houses?

When you have to take a short drive from one house to another, make sure you know the address. By analogy, know the address of the notebook, which you have written on your notebook’s binding.

In later lessons, we’ll learn how to link to articles, books, interviews and other locations that require a longer drive or even a flight. For now, we’ll settle for joining notes either within one notebook or in the three you have set up (J, P, and Q).

Finally, don’t forget your TOC’s and indices. If you are old enough to remember, the index is like the old phone books that some of you younger people may have seen on a television or movie screen and that we old folks used to carry with us in our covered wagons.

Let’s Practice

Before the bell rings and you rush for the exits, let’s take a moment to think with our hands by linking a few notes. To do so, complete these two fairly simple exercises (they’re simple because I wrote so much; if I hadn’t they’d be complicated):

Exercise One: Introduce Sister Notes

First, we’ll link One Note to an Other Note in the same notebook that Your First Note was in and we’ll call them Sister Notes. Here’s how.

Write Your Second Note

Step one:

On the page immediately after Your First Note, write one of the following:

If you are writing in your journal (J), write a reflection on what you have read in this post, such as, “This is the greatest post I have ever read because Kern obviously had a profound influence on Vince Lombardi.”

If you are writing in your Planner (P), insert a task, such as, “Complete the two exercises in the blindingly brilliant third lesson Kern includes in his note-processing series.”

If you are writing in your commonplace book (Q), copy a quotation, such as, “Fatigue makes cowards of us all.” Then add the speaker, Vince Lombardi. You should feel free, but not obligated, to write, “which shows just what a great teacher this Kern guy is.”

Step two:

Now that you have written Your Second Note, ask yourself, “Does this note have anything to do with My First Note? Are they related?”

If not, pretend it does or force it to.

For example, if you described in your journal the glory of my post and my obvious influence on Vince Lombardi’s view of cowardice and fatigue, you can turn to Your First Note to determine whether it is related to Your New Note. In the unlikely case that it is not, insert at the end of Your First Note a little addition about fatigue or cowardice, such as: “I am afraid I might not be doing this right and its wearing me out.”

There, now you have expressed your cowardice, or at least your fatigue, thereby demonstrating that you are the parent of two sister notes.

Step three:

Introduce the older sister to the her younger sister, or for the men, link your two notes.

Turning to Your First Note, either at the bottom right, beside the note in the content section, or wherever your sense of propriety leads you, insert an arrow that points to the right. Then add the number of the page on which you wrote the little sister note, Your Second Note (I’ll assume you wrote it on page 2):

→ #2

Turning to Your Second Note, insert an arrow pointing to the left and then write the number of the page on which you wrote Your First Note (which I assume is page 1).

#1 ←

Step four:

Having written a new note, update your TOC and Index.

I hope that was easy. If it wasn’t, the fault is mine because I did not make it clear enough. In that case, please ask me in the comments below to clarify, being as specific as possible. Which step confused you? Did I leave something unsaid or unclear? Was something inconsistent with what I had led you to expect? Could you not keep the bigger sister from tormenting her little sister.

Exercise Two: Introduce BFF Notes

Now let’s link between notebooks.

In what follows, I will assume you wrote Your First Two Notes in your journal (J) or commonplace book (Q) and that you have not yet used your Planning Notebook (P). To bridge the gap, I’ll show you how to write a note in P.

Thanks to “Middlescence Musings” who wrote in the comments after Lesson Two: “I am struggling to see where note taking at work (meeting notes, actions to follow up etc) will sit”. What follows only begins to address that topic, but I hope it at least succeeds in beginning so that we can kill two birds with one note: we can link two notebooks while we start to use the Planning Notebook (P).

Here’s how:

Write Your Third Note

Step one

If you don’t have it, retrieve your Planning Notebook (P).

Since you have a destination (P), select a source from among your three options: your own thoughts, something spoken, or something written.

For example, from your own thoughts, identify and write

A task or action you want or need to do

This week I will…

Today I will…

On X/X (a specified day or date) I will…

Something you love and/or are ready to commit to

I am committed to…

The one thing I love more than chocolate with hazelnuts is…

I resolve to…

A project you want to accomplish

By the end of this year I will…

By some specific date in the future I will complete X (a specific project)

From a spoken source, such as a lecture or video, identify and write

A task or action as above

A commitment or love as abov

A project as abo

Examples of spoken sources include a YouTube video by “Struthless”, a podcast by “Management Tools” and a homily from your pastor, priest, or parent.

If you prefer a written text, identify and write a note using the same pattern: task, commitment, or project.

Examples of written sources include Getting Things Done by David Allen, Overlay, Overlay: How to Bet Horses Like a Pro by Bill Heller, and Writing And Selling Your Mystery Novel by Hallie Ephron.

Urgent interruption for you Anti-Ents who are hastily running off to your notebooks: write only one note at this point!

Step two

Now that you have written Your Third Note, ask yourself, “Does this note have anything to do with My First or Second Note? Are they friends?” If not, force them into a sleepover.

For example, let’s say you are committed to ending excess aequaeousness on Saturn’s moon Titan. You have written your commitment in your note:

I am committed to ending excess aequaeousness on Saturn’s moon Titan

Noble tasks like this are inspiring, but let’s face it: they’re exhausting and lonely. So you can readily add something like, “This is going to be tiring.”

Now you can see how Your Second Note, the one you wrote in Exercise One above, relates to this Your Third Note as well as Your First Note, the one where you expressed your anxiety about doing things right.

At this point, a new uncertainty, and therefore a new anxiety, may have snuck in through the back door of your mind.

You may be asking or even just feeling, “Should I link to both of those other notes or just one?” That is a good question, but before I address it, draw back and take a look at what is happening.

Multiplication. More complicated relationships. Greater uncertainty. Chaos is creeping in.

Don’t worry. You’ve got the tools and the perspective to deal with this. We’re going to keep it simple.

Step three:

To answer your question, link the two notes that most naturally go together. In my example, I would say that the aequaeous Titan commitment in P dances happily with the fatigue note in J because they are both about getting tired.

Turning to the Titan Aequaeous note in P, either at the bottom right, beside the note in the content section, or wherever it makes sense to you, insert an arrow pointing to the right, and write the Notebook Address AND the page number:

→ J25.1 #2

Turning to the fatigue note in J, insert in a similar place an arrow that points to the right. Now write the Notebook Address AND page number for the note to which you are linking this one.

→ P25.2 #1

Step four:

Having written a new note, it is time to update your TOC and Index.

And with that, you are done.

Congratulations, you just cross-referenced your two notebooks and wrote your first planning note!

A couple questions you might have

You might be reminding me of the earlier question, “What about that third note? Should I link my third note (the one in P) to both of them?”

This will always be a judgment call, but in general I would be more inclined not to link all three of them.

Why? Because in this case you have already linked the other two notes (the two in J). When you linked the third note (P) to either of the first two (J1 and J2), you have linked it indirectly to both of them. If P takes you to J2, J2 will remind you of J1.

You have begun to generate a network among your notes that will grow like a spider’s web, often making surprising connections for you. You don’t need to overwork the threads.

To be fair, I can imagine occasions when I would link that third note (P) to both of the first two (J1 and J2).

Let’s say I have a note that I find to be extremely valuable in J or a task in P that is super important or a quotation in Q that I find powerfully compelling. In either of these cases, I might feel such a strong draw to the note that I feel compelled to make multiple links to it.

As I said above, it is always a judgment call.

Let me tell you what you are going to experience, though, because it is wonderful and it is why you must do this in analog notebooks. The time you spend thinking about which notes to link will not be wasted. Instead, it will create the friction that makes you better remember the content of your notes while simultaneously strengthening in your mind the relationships between the notes.

Or rather: not between the notes but between the thoughts you recorded on the notes.

One more thing: don’t forget about step four: you keep an index and TOC. That’s going to help a lot too.

You might also be asking, “Should I cross-reference my indices across journals?” Or, “Should I index notes from other notebooks in the index of the notebook I’m working on.”

I wouldn’t unless a note is truly extra-ordinary. I have not written such a note yet.

There is one other reason I don’t feel compelled to fill my notebooks with cross-references or to index across notebooks, but I’m about to drop a hint about an advanced lesson that you won’t get to till we’ve covered a fair bit of ground so don’t get mad at me.

Here it is:

I keep a collection of actual index cards on which I write particularly valuable notes, which I can use for multiple purposes and different areas of research or contemplation.

In that index card collection I keep (can you believe it?) an index that indexes (indicates?) my notes, both those in my notebooks and those in my card collection.

If you are obsessive enough about this, I’ll show you how to do that when the time arises. If that scares you away, don’t worry. You don’t have to learn how to do it if you don’t want to and I won’t be explaining it before you are ready.

First, practice using your notebooks for all they are worth (and that’s a lot)!

Let’s summarize:

Relationships make life messy and threaten us with uncertainty and chaos

But “One is the loneliest number that you’ll ever do.” (which must be why the band that sang that song insisted on a three dog night)

So we have to risk relationships

Harmony is more likely if we introduce people and ideas to each other after they have an address where they can rest

If they live in the same house, teach them how to communicate across the rooms and with good manners

If they live in other houses, show them how to write letters, teach them to drive, or use whatever vehicles and vessels you need to build relationships

As you do, you will bring peace to your mind and very possibly to the world around you

Some of this applies to note-processing by analogy so if we practice with note-processing it might help us bring harmony to our minds and our communities

Because the world is a symphony and you have a part to play

A closing thought

I came across this quote from Confucius and I wonder whether it fits our discussion. Do you think it does?

It is the spirit of charity which makes a locality good to dwell in. He who selects a neighborhood without regard to this quality cannot be considered wise.”

Analects, P.22 in my version.

I just sort of made that up. Really, I anglicized it. It is Greek for “hard to understand.”

Thank you for this. I had begun cross referencing in the body of the note, but arrow/address in lower right corner is much more visible. Re Underlining … I might experiment with this, but I got only four of the five colour/purposes: green,orange,pink,blue. What would be the fifth? Merci

I've worked through these 3 lessons--it wasn't hard since it only required a few small yet thrilling shifts from how I already use notebooks--and I find myself anticipating with such eagerness the lesson that will explain what the 4 pen colors are for.