Mastering Note-Processing, Lesson 1: Setting Up Your Notebooks

Includes Pictures!!

From Cicero to Erasmus to John Locke to Jonathan Edwards to the madman who helped the professor write the Oxford English Dictionary, every influential thinker since the invention of letters had a secret formula that made him effective: he knew how to do notes.

Note-taking is probably the single most necessary skills for careful thought, and yet beyond certain rudimentary skills taught in the most advanced classes (where students have often already developed their own), we don’t teach our students effective ways to do it.

I want to contribute to a solution, so I am writing this civilization-saving series for those of you who want to think well and bless others with what you discover.

If you are new to note-taking, you should attend to the most important thing: just write notes. Don’t worry about all the refined skills the master note-takers perform with dizzying ease. Just write notes.

Then, after a while, one of two things will happen.

You may find that your approach perfectly satisfies your desires. In this case, you should continue as you started, and you should thank God that you matched your own disposition to the available tools and so wrote the notes you need.

Or something very different may occur. You may find that the tools and approach you have adopted works quite well for some things but not for others. In that case, you will either try to find solutions, settle into to an unsatisfactory situation, or stop writing notes altogether.

This post is for those of you who have discovered that your tools and actions leave you dissatisfied or even frustrated, so you want to refine your note taking system and are seeking solutions. You’ll find them below!

Review for Context

In my two previous posts I insisted that if you want to take good notes, useful for your whole life, you need to do five things:

1. Include an alphabetically arranged bibliographic section for sources

2. Include an alphabetically arranged topic index to find notes when you need them

3. Include a numerically arranged (or maybe alphanumeric) content section in which you include notes and materials

4. Separate specific notes (I think the buzzword for this these days is "atomic notes") from their sources into that alphanumeric content section

5. Do it by hand in the analog world

I also claimed that when I have used all five I have been creative, productive, and, at least relative to me, useful to others.

Showing that people process notes for three general reasons, to gain insight, to produce something, and to remember, I promised to show you how to successfully accomplish these three ends if you would go out and secure three notebooks, one for each purpose.

In this post, I keep that promise and begin a journey to the glory-land that meets all five conditions described above.

Your First Big Decision and the Inescapable Challenges

When you start keeping a notebook, the first big decision you need to make is whether to use one or many. Some people can satisfy with one notebook all their note-taking needs. Typically, they use fairly elaborate systems within that one notebook, such as bullet journaling or common-placing in the broadest sense. Others find they need different journals for different kinds of notes or for different purposes.

Below, we will look at particular kinds of notes and the diverse reasons people take them. But before we do, we should look at something universal that applies to every kind and purpose of note-taking: the three inescapable challenges of note-taking.

If you are the sort of reader who can set aside her curiosity about what will follow in this gripping drama, take a moment to do a little exercise: write down three or more things that you find challenging when it comes time to deal with your notes.

If you are a normal reader who would rather have the riddle answered without trying to solve it, I will now tell you what you would have written if, like the more disciplined among us, you had paused to write them down. For we all have three challenges, and the value of any note-processing system is its ability to overcome these three challenges.

to write a note when the noteworthy idea enters your mind.

to find the note when you need it.

to do something with the note when you find it, such as, write something fresh and compelling, deliberate over an issue, go fishing, or contemplate an idea.

Because my goal is to help you master the means to overcome all three challenges, I pulled a masterful and clever ploy just up above. Did you notice it?

Until the last sentence before the list, I kept talking about note-taking, note-taking, taking notes, etc. Then, I tricked you and changed the phrase to note-processing1. I trust you can see the significance of the change. Taking notes is fairly easy, if you have the will and sufficient skill to pick up a pen and start writing on a slip of paper. But how will you find it when you need it? And how will you be able to use it when you find it?

Those are real challenges, if only because when you meet them you are not doing it for your present self, who simply wants to capture that world-changing, fleeting thought before it flies away like an owl at dawn. Making the note findable and usable is an act of care for your future self, that more mature person who has to live with all the decisions your present self makes today.

At the same time, your future self wants to care for your present self, knowing that confusion and exhaustion have a way of lingering.

Consequently, the note-processing system you use should — no, must — achieve three ends:

Your present self should — no, must — be able to easily write a note with the tools at hand.

Your present self must have an effective, if not easy, way to dispose the note at an address or in a location that your future self can easily find.

Your future self must be able to manipulate the notes, to move them around, to physically arrange and rearrange them, so as to discover refreshing insights, solutions to problems, resolutions to discords, surprising associations, clear instructions, processes, even categories of information.

To please your future self, who can only work with what you give him, you must identify tools and a structure that make it easy to record a note while simultaneously easing the trial of the second need (giving the note a home), and following a procedure that makes it possible and enjoyable to meet the third need (writing something that will please you).

In what follows I will show you the tools, structure, and procedure that will make you an effective processor of notes.

Time to Exit?

At this point, I shall offer some of you an easy exit ramp. If you are new to note-taking, if you do not feel the need for this apparently complex system (it isn’t really; it’s astonishingly simple), or if for any reason you want to take a different road, you should feel free to stop here. Find yourself a notebook you like, write notes to your heart’s content, and be happy. If you ever decide you’d like to become a writer or at least a note-processor, you will be more than welcome to rejoin the journey on the other side of the bridge.

On the other hand:

Why Three Notebooks?

Now, Renee, since you have decided to continue on this journey with me, I will turn in the direction of the promised post: how to set up the three notebooks you secured for this project (Anybody else coming along?).

You may have wondered, “Why three notebooks? Why not just one? Why not 21?”

Here’s why:

You write notes of many different kinds and there are almost certainly people who write kinds of note that you and I have never bothered with or maybe even conceived. Somebody somewhere has developed a specific notebook for every conceivable kind and even some that are inconceivable. Here are some of the more common:

Diary

Pensees

Quintilian commonplace

Copy work

Scrapbook

Journal

Planning

Commentary

Compendium

Chapbook/draftbook

In my view, your experience will tell you which notebooks you need. You can go along with one kind of notebook, perhaps for years, but then eventually a bubble starts to form on the outer edge that tells you a new kind of notebook is about to be born. Perhaps you have kept something you call a journal, but now you are finding that you want to separate your own reflections from quotations that you draw from things you read. That is a good time to start a second notebook.

However, the fact that you have read all the way to this paragraph tells me that you are beyond the need for one notebook. But which ones should you start? All of them? Impossible and unnecessary.

If you go through the list, you may notice that they can be categorized, at least loosely, under three different purposes. You almost certainly take notes:

for reflection/insight

for planning (career, life, writing)

for quotations (a commonplace2)

These three align quite nicely with the three purposes we identified in the previous post: insight, production, and recollection.

Therefore, you will find it at least temporarily satisfying to set up three notebooks. I call them

A journal (“J” for short)

A planning notebook (“P” for short)

A Commonplace notebook (“Q” for short; Q stands for quotations)

You should feel free to create a specific notebook for any other purpose you feel pressing its way out of the womb of another notebook, but in what follows I will describe only those three.

Setting Up Your First Notebook!

With that, it is time to set up your notebooks. This part is actually pretty easy, so I’ll just describe the process. In later posts, I’ll get into the details of how to capture, sort, and use notes in the three kinds of notebook.

You should be aware that a sudden and shocking twist in the plot is coming not far from now. Once you have gained some practice with your notebooks, I am going to show you that they are not adequate to the requirements of your genius and, while you will continue to use these notebooks for the rest of your long and thoughtful life, you will ascend to a higher order of being and productivity. I will show you how. However, before you can be a monarch, surveying your meadow, you must be a caterpillar crawling on your branch. In fact, you’ll have to be a caterpillar weaving your own little chrysalis, your own private cave, into which you will have to crawl so that you can experience a metamorphosis. But ah, those wings!

Anyway, I got carried (blown?) away for a moment contemplating your coming glory. Back to the notebooks.

To set them up, you need to do four simple things:

Set aside a few pages at the beginning for a table of contents.

Set aside a few pages at the back for an index.

Set up a few pages after the TOC in the optimal note-taking format.

Write an “address” on the notebook’s binding.

Table of Contents

First, a table of contents. Some notebooks give you a pre-structured TOC, like the Leuchtturm 1917. Some don’t. It doesn’t matter.

I have found that three pages works for me, but there is a qualifier to that which I will mention below. You may want to start with 5 or 6 pages in your first notebook.

When you start adding notes in the main content section, you should not list every page in the TOC, anymore than a book would. If you write five pages of notes on, say, the flowers you want to add to your garden next spring, write the number of the first page on which you start writing notes and give it a title you find helpful, such as “43 flowers to add to the garden in the spring.”

For now, however, all you need do is set aside three to six pages for a TOC. Write TOC in the top right corner and smile as you check this task off your list.

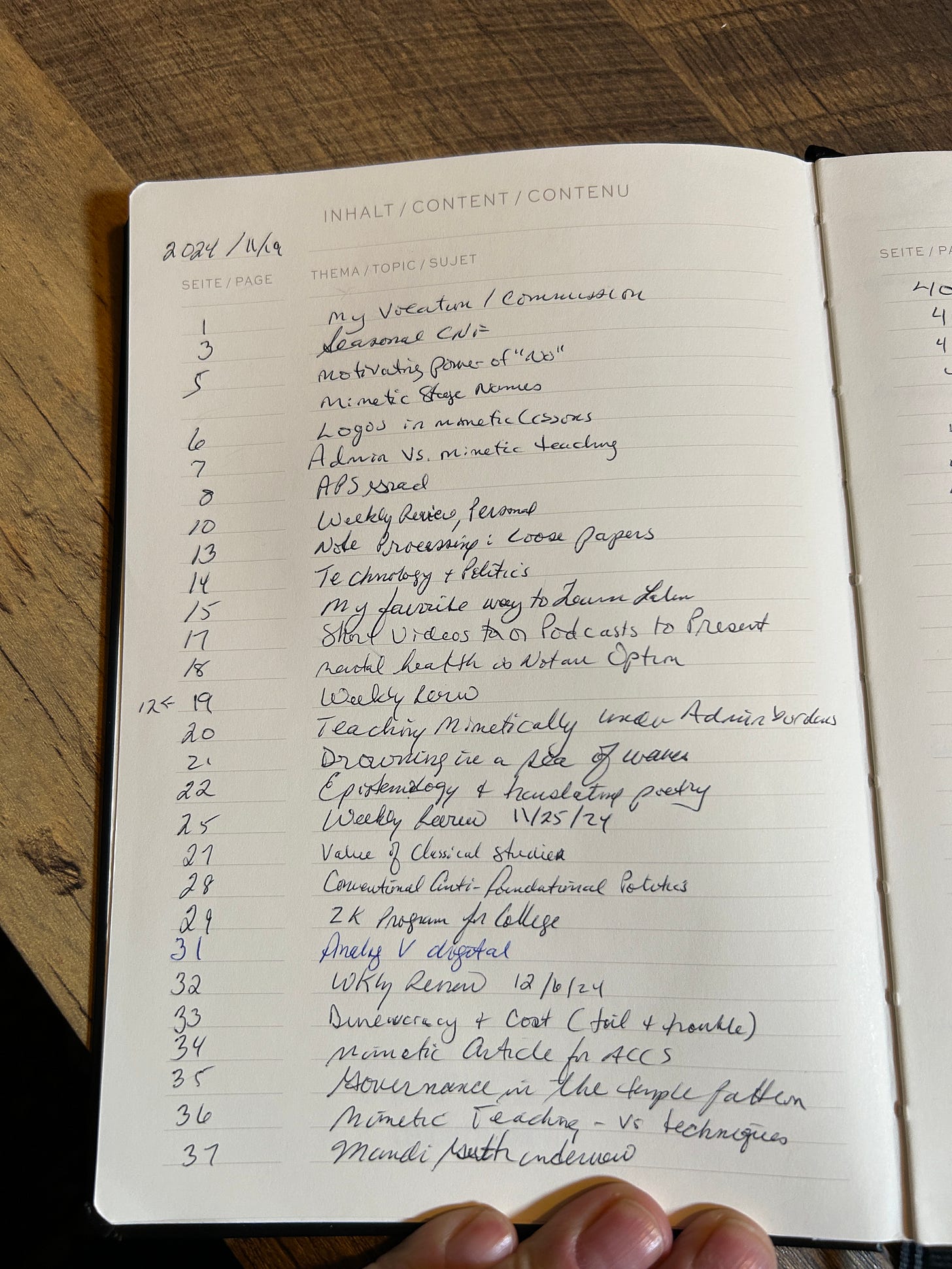

Here’a a completed TOC from the journal I started on 11/19/24:

Index

Now turn to the back of your notebook and set aside pages for an index. This is a little more complicated than the TOC. Your future self will sing your praises when you give her a proper index, which is the key to finding things. You will create your own index in the pattern that scholarly or carefully written books create them: topic and page number. As with the TOC, I am running a little ahead. All you need to do right now is create pages for the letters.

Unless you write with large, sweeping letters, this is how I recommend you set up the index:

On the last convenient page, put a Capital A in the top left corner and a capital B in the bottom left corner. Turn to the next inner page, and inscribe a capital C in the top left corner (unless you prefer the right) and a capital D at the bottom. Continue to add two letters per page until you reach Z, but with these slight adaptations:

Q and R should go together at the top of one page, and S should be inscribed at the bottom.

V and W should be placed at the top of the last index page and XYZ should be inscribed at the bottom.

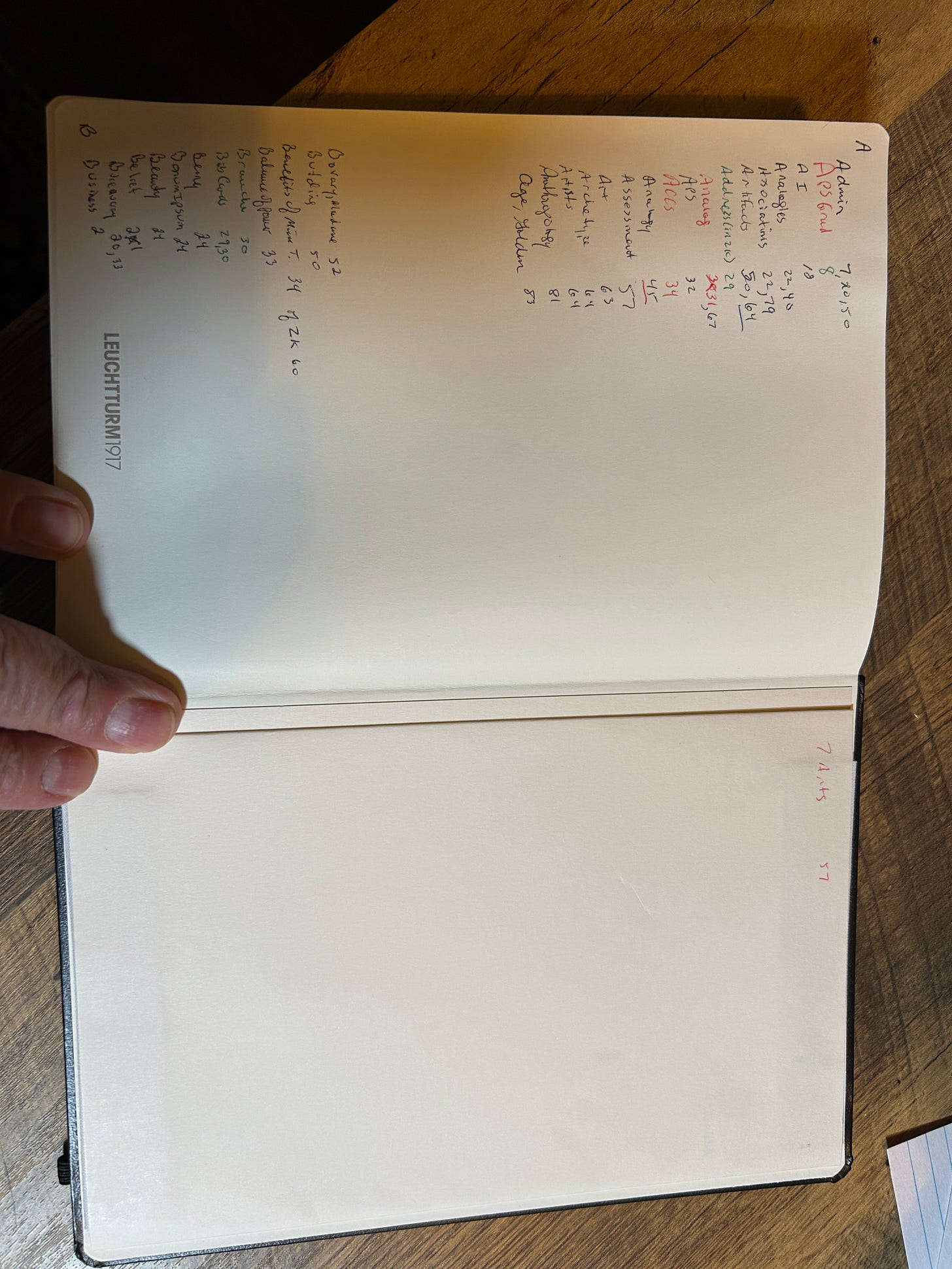

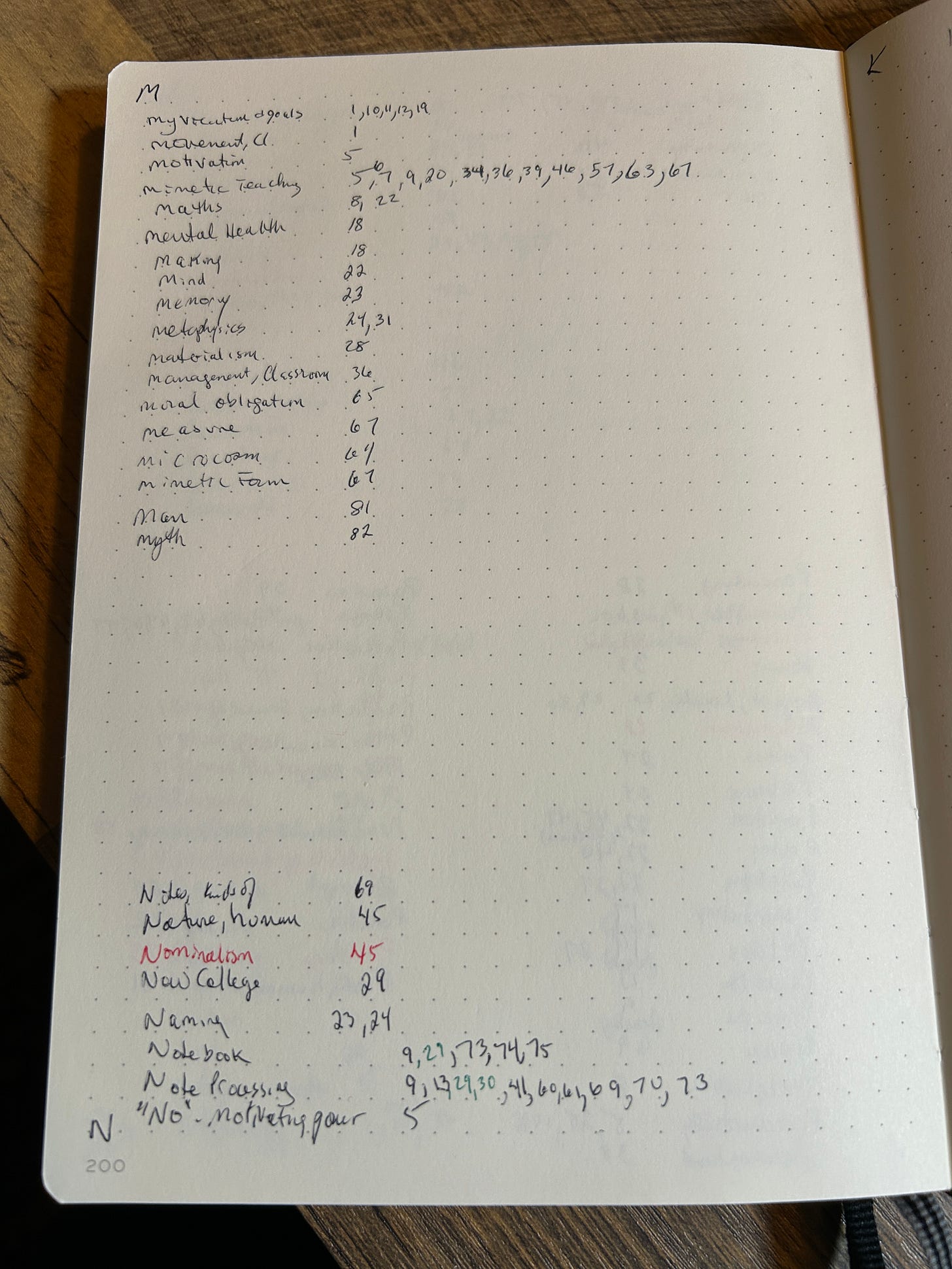

Here are some pages from my index:

That is your index. All done. Check it off your list!

Pages

Now let’s set up a few pages.

I begin with a warning. My past self was not very conscious of the future, which is where I lived back then. As a result, he tried to fill every millimeter of paper space with words and lines and scribbles. I think he secretly hated me and wanted to install speed bumps all over the highway of my mind. More likely, he was so anxious to extract his thoughts from his head that he never thought about how somebody else (me) might find them and, having done so, give honor to those worth honoring.

Net effect: lots of wasted paper, hundreds of pages of notes that have been incinerated (no, really), and probably at least an occasional good thought that I’ll never come across.

White space is your friend. Remember, you are writing notes so that you can find them easily. The index we discussed above will help with that. So will eye-friendly pages that let you find easily what you are looking for without an elaborate game of hide and seek at the worst possible moment.

Therefore, I do two things to optimize main content pages, and I would urge you to do them as well, even though one of them is going to be hard for you to buy into (you’ll see why in a moment).

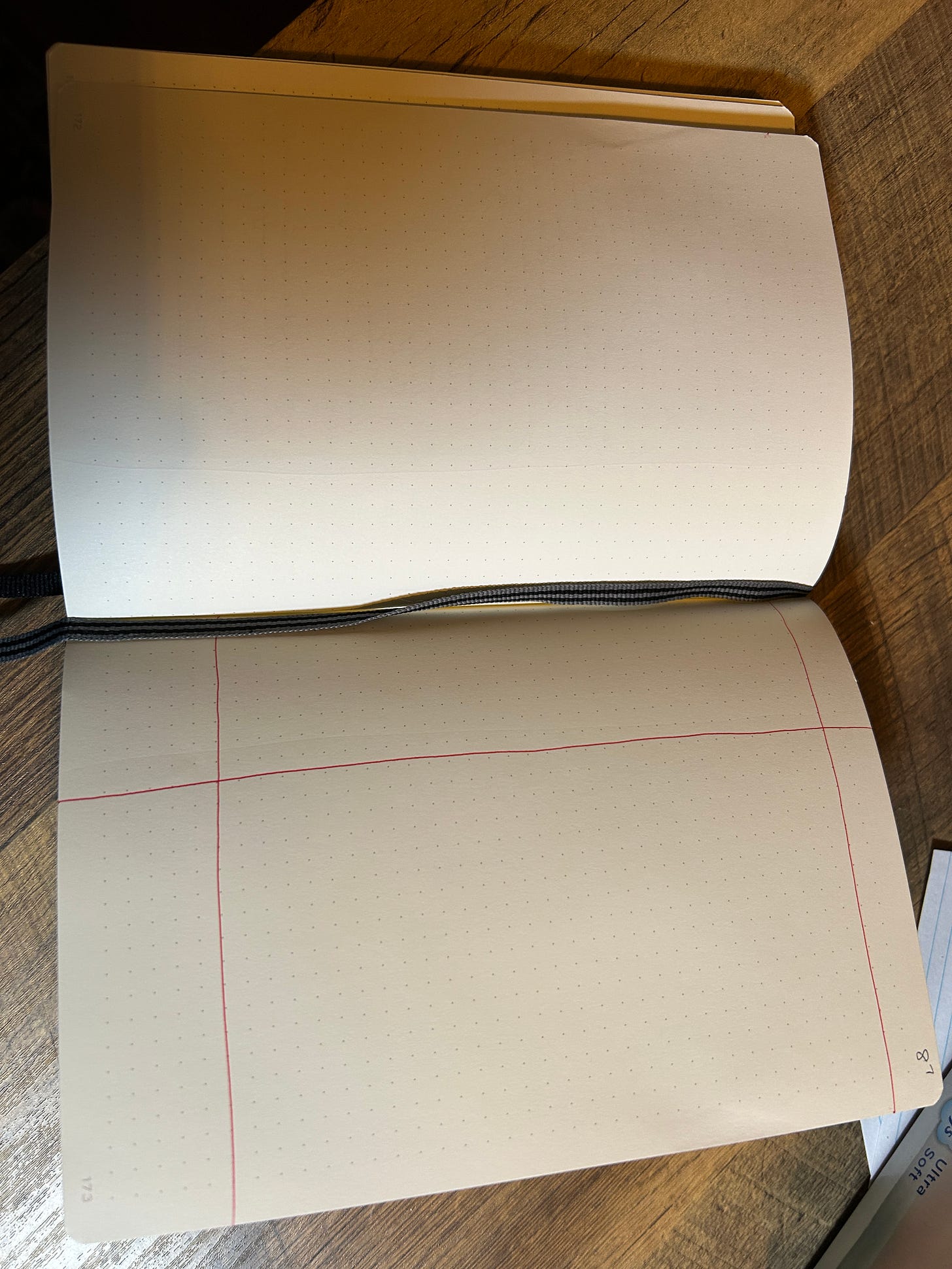

First, set up each page in a pattern similar to the Cornell pattern. You can find variations on exactly how to do this (Google away if you like!), but here’s the basic idea:

1/3 of the page from the left, beginning at the top, draw a vertical line straight down the page until you are approximately 20 or 25% from the bottom. Then stop. Personally, I write these lines free-hand because I’m not fussy that way. But if you are a perfectionist with a strong will and three more seconds to live than I have, rule away!

If you do want to be that detailed, which I respect, try to stay ahead of yourself by always setting up note pages before you need them. Remember, the first of the three challenges was to be able to easily record the note when it comes to your mind. If you have to set up the page when the spirit calls, you’ll probably lose your inspiration while you do so.

Now, in an emergency, when for any reason you don’t have a page ready for note-taking and an idea descends upon you like a snow white dove, don’t worry about it. Just start writing as close as you can to the place where you would if the page was ready, and then let the note flow. You will gradually learn that this whole approach is VERY forgiving.

Anyway, now that you have inserted a vertical line, you will want to make two horizontal line: one near the top and one where the vertical line stopped on its way to the bottom.

Even here, if you accidentally or even deliberately traced the line all the way to the bottom of the page, don’t lose any sleep. Make the horizontal line about 20% up from the bottom. The 20% is an estimate and I doubt I make mine that far up. Here’s a picture of one I set up (note that my vertical line goes all the way down while the top horizontal line might well be too high; have I mentioned that this approach is forgiving, so you should be too?):

You now have a page with five or six sections. We’ll go into how you’ll use those sections in a later post. Here I’ll just add this starter instruction: the main box, from the vertical line to the right edge of the page and between the two horizontal lines, is your main content box. Here you will write the note as it comes to you. To the left of that, in the 1/3 of the page left of the main box, you will put cues and Q’s (questions), words that serve as finders or outline points. At the top, you will give the page a title. And at the bottom you will summarize and/or hyperlink your page.

If all of that sounds terribly complicated, that is because I’m explaining a physical process in words that will be much easier when you see it, which I have proven by showing you the picture above.

Incredulous!

Here comes my second instruction, the one you won’t believe, the one you will consider irresponsible, the one that will make you want to quit this whole procedure, and the one for which you will some day stand beside my grave with tears skiing slaloms down your fair cheeks, and you will say, “How can I thank you enough; how could I have doubted you?" And, like wisdom herself, I will lie there in pace, chuckling softly in my silent quietude.

Ready?

Here it is.

NEVER write on the left-side page.

To quote every self-important politician since President Obama made it cool, “Look,” you are going to have to take this on faith. In me.

All I can say here is, I cannot count the number of times I have been relieved by the thoughtfulness of my past self who left that page blank for me. How easy to find things. How easy, much later, to add emergency notes. How lovely the sight of blank paper!

NEVER write on the left-side page (which is one reason I only need 3 pages for my TOC)

Home Address

At last we come to the binding itself. You may recall from the previous post that I mandated a notebook with at least a 1/4 inch binding. That is because when you want to find something, it will not be enough to know where it is. You will also have to know what it is when you look at it. To make that easy, you will give your notebooks a name and address.

Above, I mentioned that I call my journals “J”, my planning notebooks “P”, and my commonplace books “Q”. Here’s how that helps.

To the binding of each notebook, I add a very simple address based on the date when I start a notebook, always putting the year before the month. Thus:

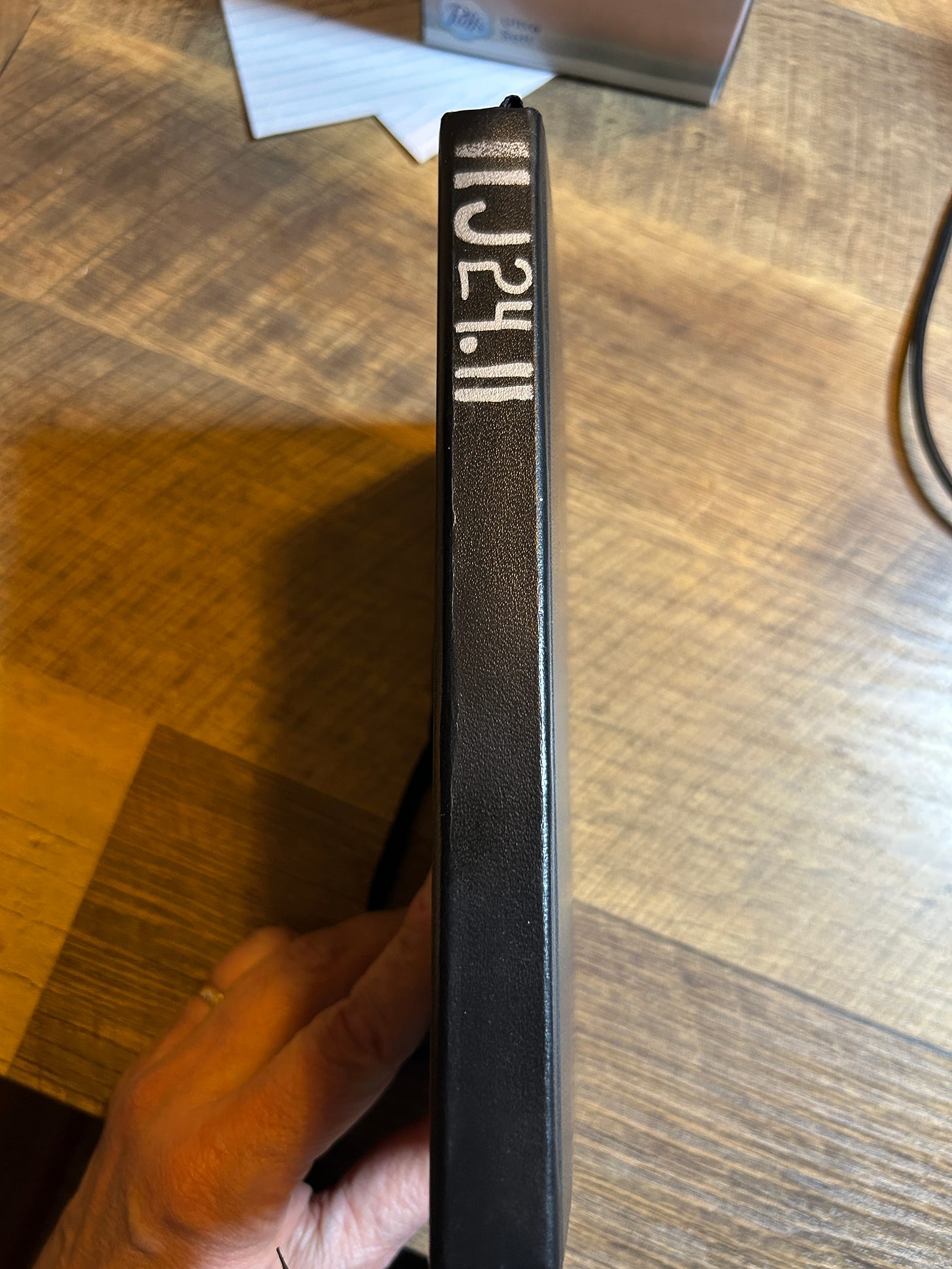

J24.11 refers to a journal that I started in November of 2024.

P25.1 refers to a planning notebook that I started in January of 2025.

Here’s the binding of the journal I started on 11/19/24. Note the order of the numbers on the binding (Be careful. I have taken to making two straight lines at the top of my journals and I’m not sure why. I think it must be because I decided it looks better. Unfortunately, it also makes it look like there’s an 11 at the top. Just ignore those two lines).

The address of this notebook is J24.11.

I don’t bother dating commonplace books because they serve a more timeless purpose. But if you want to start one now, I recommend:

Q25.1

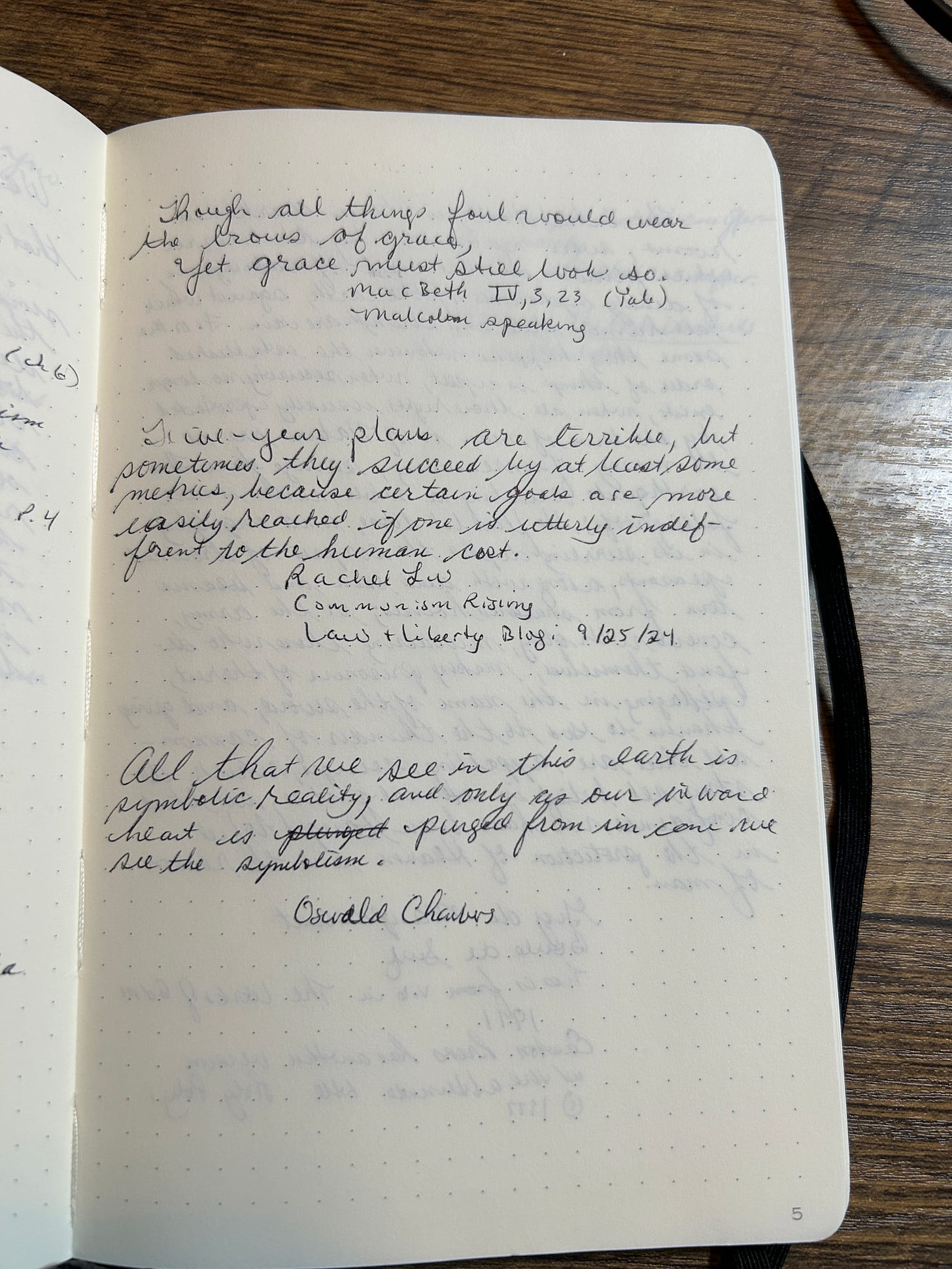

I also don’t set up the pages in a commonplace book like a P or J notebook, using the more or less Cornell pattern. I just write the quotations and add the author and source. You can call me a fraud and demand a refund because of my inconsistency if you want. Heck, maybe my future self will agree with you and he’ll change my mind. In the meantime, to make up for my wickedness, here’s a page with some quotations straight out of my commonplace book for your reading pleasure:

Qualifiers

I’ll wrap this up with a couple qualifiers and a summary, followed by an appeal for cold hard cash and some revolutionary documents.

First of all, I have adopted a dictatorial tone in this post because I am an insecure gamma male and because I want to start you off with very specific instructions, lacking in nuance and judgment. In time, you’ll break free and make all sorts of changes to suit the tools to your own purposes. That’s fine. In this early stage, I’m concentrating on the universal elements so that you have the most basic ingredients as clear as possible. The more closely you “follow the rules” now the better you’ll understand how to twist them later.

Also, I’m giving you a process that is as comprehensive as I can make so that you can practice doing things too completely and then pick up the things you like and drop the things you don’t.

As you put these steps in place, keep the goal in mind: to produce a written text that people will find worth reading. That is what I’m trying to help you do, and it’s what I hope I’ve been able to do by way of example. This thread is not oriented toward note-taking, but toward producing something with your notes: a book, an article or series of articles, podcast interviews, personal letters, personal contemplations, whatever.

Summary

As a thinking person, you write many kinds of note, but they can be categorized without undue harm into three main groups, which we put into three kinds of notebook: a journal for insight, a planning notebook for production, and a commonplace for recollection.

When you set up your notebooks as I have shown you, you will please both your present and your future self, because 1. you will be able easily to write new notes as they descend upon you, 2. you will be able easily to find them when you need them, and 3. you will be able readily to turn them into valuable projects when you find them.

Threats and Promises

In my next post, deo volente, we’ll take a closer look at how to take the perfect note, thus overcoming your first challenge.

Nobody is trying to escape the reductions of our disenchanted and desacralized age more earnestly than I am, so this phrase “note-processing” bothers me as much as it might you. However, there is a process, and it is a real one, so I don’t mind using the word to name something appropriately. Just be careful not to mechanize the concept of a process. I’m describing something more like an art than a technique or a technology.

In a later post, I will address the use of the term commonplace. Here I am using it as Quintilian did and as Renaissance note-takers tended to: a collection of quotations.

I bought a book about using an index card system last year. It’s huge, and the instructions made my head hurt which was disappointing because I need a system I can use, which you have started to outline! Thank you!!! It also means I can buy more stationery which my past, present and future self are very happy about. Looking forward to the next lesson

Thank you for taking the time to walk through this. I am trying to start taking careful notes as I read this year, and this layout helps immensely. I will be taking the broad strokes of this for a book of Reflections and a book of Quotes (both pocket sized for on-the go thinking) and I am looking forward to seeing how it plays out.